Introduction

Turning the page on election “fundamentals,” our course now turns to examining presidential campaigns and their impact on voter behavior. Campaigns capture the attention of thousands of voters across the country, helping them learn about political candidates and influence the electoral process.

My blog this week focuses on the “air war” between campaigns: advertising has both the power to persuade and mobilize voters to the ballot box. First, I create a series of descriptive figures and tables to assess past trends in campaign ad spending on both the national and state levels. I then update my models to predict both the national two-party popular vote and the Electoral College for the upcoming 2024 election.

Examining Ad Spending in Past Presidential Elections

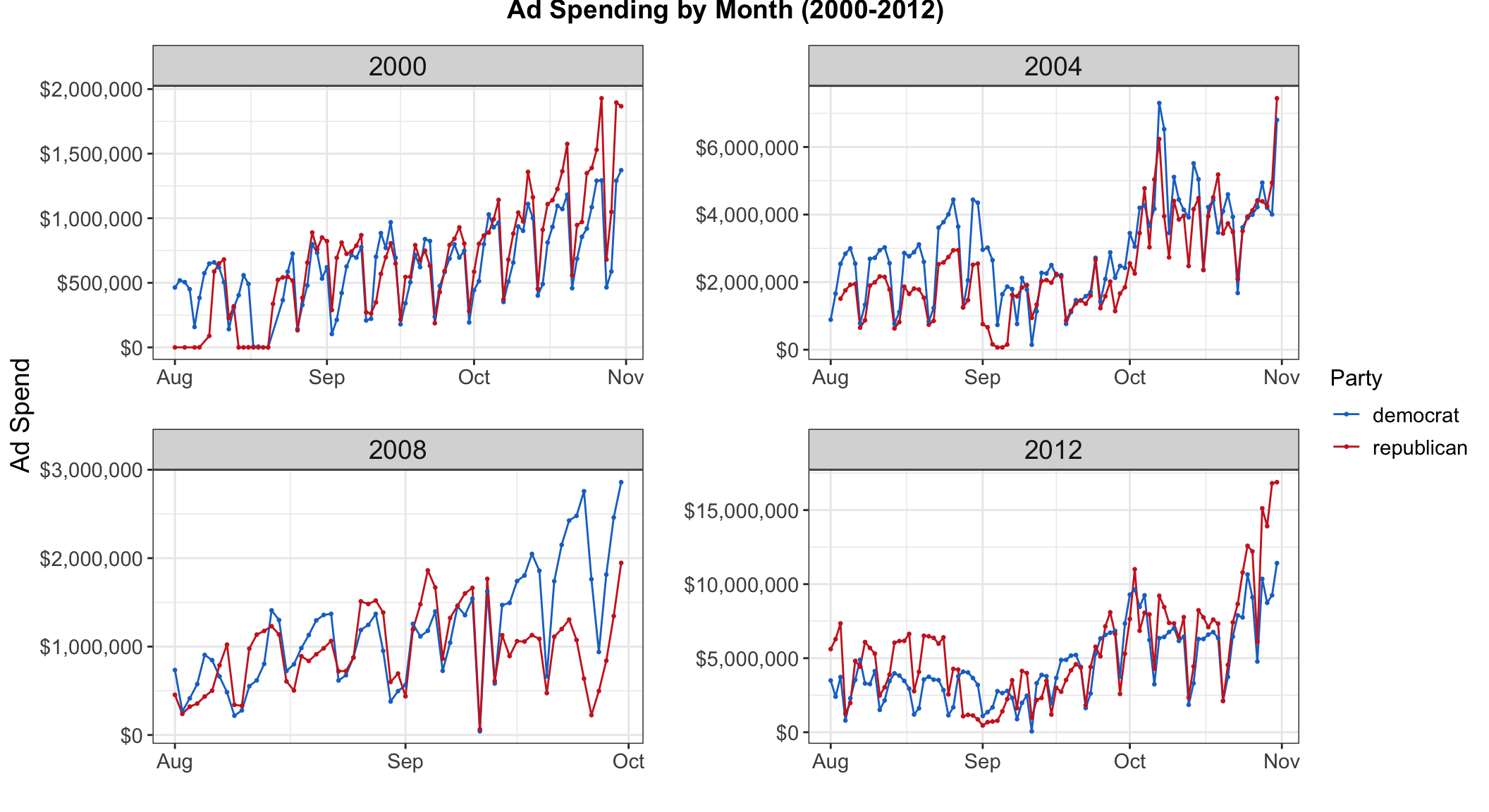

Before we get to predictions for 2024, let’s take a look back at campaign ad spending in previous elections. The following visualization plots campaign ad spending by month for the presidential elections from 2000-2012.

Unsurprisingly, campaigns increase their funding for ads closer to the election — ad expenditures increase over time for all four elections. It’s important to note the scale of each individual plot here: Senator Mitt Romney’s campaign surpasses 15 million in ad spending by November 2012, which is significantly higher than the maximum spending of the three previous elections (2 million in 2000, 6 million in 2004, and 3 million in 2008).

However, does increased ad spending translate into an electoral advantage for the candidate with more air time? Focusing on the 13 potential toss-up states for the 2024 election (from last week’s blog), I identify the candidate with the higher state-level ad spending from the 2004, 2008, and 2012 presidential elections. The “match” column indicates whether or not that candidate with the higher state-level ad spending won the state.

| State | Spending Advantage | Match | Spending Advantage | Match | Spending Advantage | Match |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arizona | Democrat | No | Republican | Yes | Republican | Yes |

| Florida | Democrat | No | Democrat | Yes | Republican | No |

| Georgia | Democrat | No | Democrat | No | Republican | Yes |

| Michigan | Democrat | Yes | Democrat | Yes | Republican | No |

| Minnesota | Democrat | Yes | Republican | No | Republican | No |

| Nevada | Democrat | No | Democrat | Yes | Republican | No |

| New Hampshire | Republican | No | Democrat | Yes | Democrat | Yes |

| New Mexico | Democrat | No | Democrat | Yes | Republican | No |

| North Carolina | Democrat | No | Democrat | Yes | Republican | Yes |

| Pennsylvania | Democrat | Yes | Democrat | Yes | Republican | No |

| Texas | Democrat | No | Republican | Yes | Republican | Yes |

| Virginia | Democrat | No | Democrat | Yes | Republican | No |

| Wisconsin | Democrat | Yes | Democrat | Yes | Republican | No |

As we can see in this table, candidates that spent the most on ads in the 13 selected states did not always end up carrying that state. This correlation (at face value) appears to the strongest in the 2008 contest, where the candidate with the state-level spending advantage won 11 out of 13 states; That’s a much better performance than the 2004 (4 out of 13) and 2012 presidential elections (5 out of 13).

Looking at 2020, this table presents at the number of campaign ad airings between April and September in each of the 13 states, arranged from the greatest to lowest total cost. The table also indicates which candidate had the air advantage (greater number of aired ads), as well as who ultimately won the state.

| State | Biden Airings | Trump Airings | Total Cost | Air Advantage | State Winner |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Florida | 112982 | 77756 | 137821820 | Biden | Trump |

| Pennsylvania | 89612 | 62292 | 95155100 | Biden | Biden |

| North Carolina | 52045 | 57299 | 66771000 | Trump | Trump |

| Wisconsin | 69132 | 51951 | 56274430 | Biden | Biden |

| Arizona | 48401 | 35802 | 55601590 | Biden | Biden |

| Michigan | 73510 | 25243 | 47117340 | Biden | Biden |

| Georgia | 245 | 37378 | 19280010 | Trump | Biden |

| Minnesota | 16424 | 11546 | 15349730 | Biden | Biden |

| Nevada | 13527 | 6492 | 7709440 | Biden | Biden |

| Texas | 731 | 606 | 707840 | Biden | Trump |

| New Mexico | 18 | 1024 | 200380 | Trump | Biden |

| New Hampshire | 167 | 0 | 190010 | Biden | Biden |

| Virginia | 32 | 0 | 3920 | Biden | Biden |

There are only 4 cases here where the candidate with the air advantage went on to lose the state: President Biden had the air advantage in both Trump-won Texas and Florida, while Trump had the air advantage in Biden-won Georgia and New Mexico.

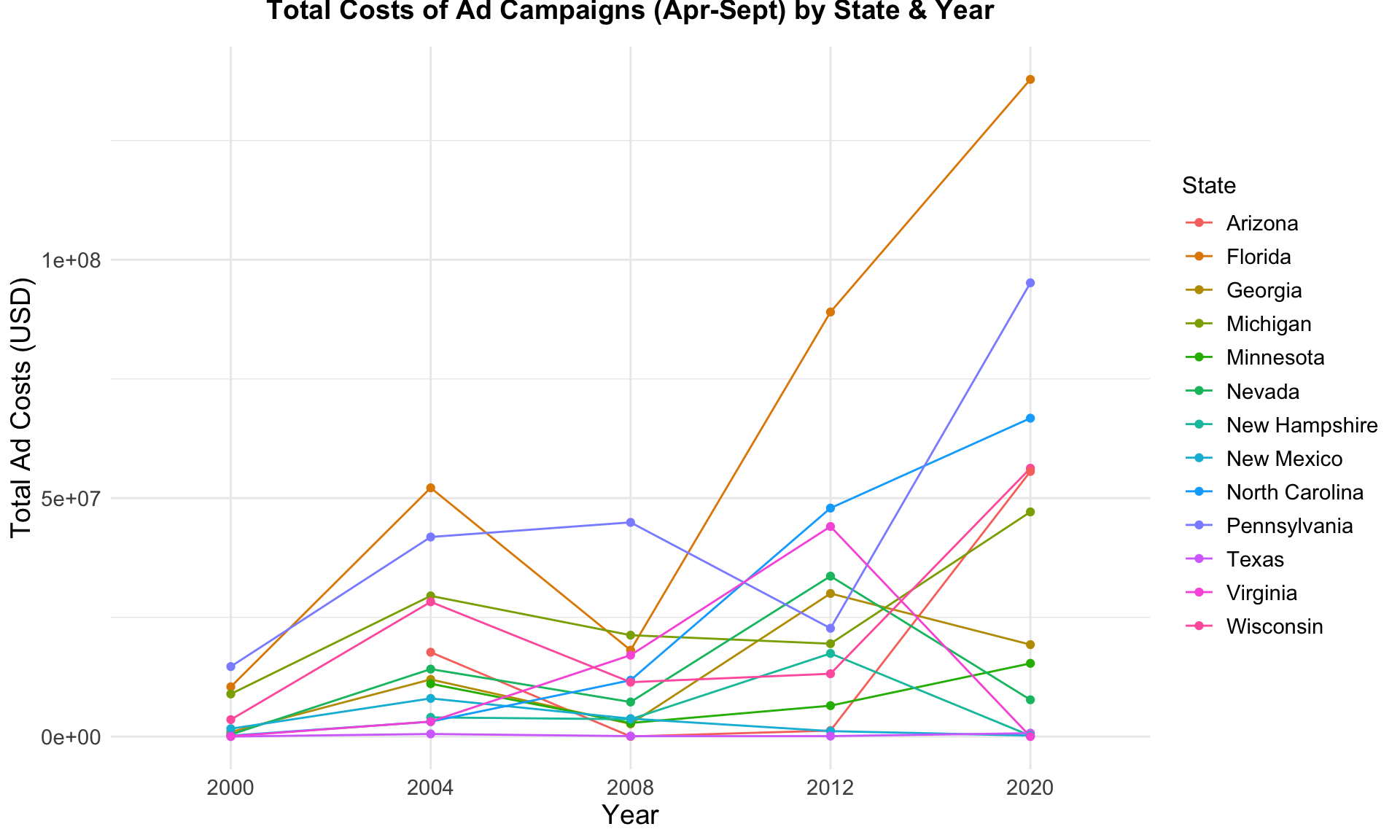

Notably, Florida (138 million), Pennsylvania (95 million), and North Carolina (66 million) have the highest total ad spending between April and September 2020. How has total ad spending in these 13 states changed over time? The next line plot visualizes trends in total costs of ad campaigns over 5 presidential elections (2000, 2004, 2008, 2012, 2020). We do not have access to data from 2016, so spending in that election year is omitted.

First and foremost, total ad spending in Florida has been on a strong upward trend since 2008 — candidates put the most money into Floridian ads in 2004, 2012, and 2020. It’s also interesting to note the states that have increased in total ad spending from 2012 to 2020, mainly Pennsylvania, North Carolina, Wisconsin, Arizona, Minnesota, and Nevada in addition to Florida. Those states now comprise our core battleground states, which makes sense why candidates are increasingly investing in ads aired there.

Although we do not yet have access to full campaign ad spending for the 2024 election, CNN reports that this year’s spending to elect a president and members of Congress will hit at least 15.9 billion USD — the nation’s most expensive federal election to date. Campaign ad spending is only expected to pick up as we near the election: groups backing Vice President Harris have reserved 332 million USD worth of airtime for TV and radio ads, compared to about 194 million USD from Trump’s supporters. The spending race in the swing states is particularly interesting to track as the Harris campaign is set to spend 109.2 million USD to the Trump campaign’s 101.7 million USD in Pennsylvania alone.

National Two-Party Popular Vote Model

Next, I shift back to updating my electoral predictions for the national two-party popular vote share. Building upon my model, I add a new variable to the regression: the national two-party percentage of voters. We know that partisan affiliation is a strong demographic predictor of turnout and voting behavior, which is why I wanted to include it in my model. This data set was kindly put together using data from Pew Research Center and Gallup by my incredible classmate, Alex Heuss! The regression table for the new national popular vote share model is below.

| National Popular Vote Share for Incumbent Party Candidate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Estimates | std. Error | CI | p |

| (Intercept) | 28.61 | 6.95 | 12.18 – 45.04 | 0.004 |

| GDP growth quarterly | 0.68 | 0.24 | 0.12 – 1.25 | 0.024 |

| RDPI growth quarterly | -0.54 | 0.32 | -1.29 – 0.22 | 0.135 |

| sept poll | 0.43 | 0.11 | 0.18 – 0.68 | 0.005 |

| two party percent | 0.04 | 0.08 | -0.15 – 0.24 | 0.602 |

| incumbent | 0.24 | 1.50 | -3.31 – 3.79 | 0.875 |

| Observations | 13 | |||

| R2 / R2 adjusted | 0.881 / 0.797 | |||

With an R-squared value of 0.88, this table suggests that my model is a strong predictor for the incumbent party candidate’s national two-party popular vote share. That being said, Q2 GDP quarterly growth and September national polling averages are the key predictors in this model; the Q2 RDI quarterly growth, national two-party percentage, and incumbent status coefficients are not statistically significant, indicating the lack of a clear effect on the incumbent party’s vote share in this model. I then use this regression model to predict Harris’ share of the national two-party popular vote.

| Prediction | Lower Bound | Upper Bound |

|---|---|---|

| 53.29 | 46.86 | 59.72 |

Here, Harris is predicted to win the national two-party popular vote by 53.3%. This is consistent with the results from my previous blogs, which all have Harris winning approximately 53% of the popular vote. Notably, however, this week’s prediction intervals are slightly larger than those of the last two weeks’ predictions. Going forward, I may simplify my national model by focusing solely on Q2 GDP quarterly growth and September polling averages, which may help to reduce over-fitting or noise.

State Two-Party Popular Vote Model & Electoral College Prediction

I now make my Electoral College prediction for this week. To do so, I adapt the model I’ve used to predict the Democratic candidate’s state two-party vote share in previous weeks: I add October state-level polling averages as another coefficient in my mostly poll-based state model. This is a regression table for the Democratic candidate’s state-level popular vote share and state-level polling averages in both September and October (weighted by weeks left before the election) for the presidential elections from 2000-2020.

| Democrat's State-Level Popular Vote Share | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Estimates | std. Error | CI | p |

| (Intercept) | -0.27 | 1.10 | -2.43 – 1.90 | 0.810 |

| sept poll | -0.35 | 0.15 | -0.64 – -0.06 | 0.018 |

| oct poll | 1.46 | 0.14 | 1.18 – 1.73 | <0.001 |

| Observations | 291 | |||

| R2 / R2 adjusted | 0.882 / 0.881 | |||

Once again, the relatively high R-squared values of 0.88 suggest that state-level September and October polling are strong predictors for the Democratic candidate’s two-party popular vote share for that state. More specifically, the model shows that October polling is a strong and significant predictor of the Democrat’s state-level popular vote share, while September polling has a smaller, negative effect. The prediction for 2024 follows.

| State | Prediction | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | Winner |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arizona | 51.51 | 44.59 | 58.43 | Harris |

| Florida | 50.47 | 43.56 | 57.38 | Harris |

| Georgia | 51.85 | 44.93 | 58.77 | Harris |

| Michigan | 52.93 | 46.01 | 59.84 | Harris |

| Minnesota | 54.87 | 47.94 | 61.79 | Harris |

| Nevada | 52.93 | 46.01 | 59.84 | Harris |

| New Hampshire | 56.26 | 49.33 | 63.18 | Harris |

| New Mexico | 55.27 | 48.35 | 62.19 | Harris |

| North Carolina | 52.25 | 45.34 | 59.17 | Harris |

| Pennsylvania | 52.86 | 45.95 | 59.78 | Harris |

| Texas | 48.76 | 41.85 | 55.68 | Trump |

| Virginia | 55.01 | 48.09 | 61.94 | Harris |

| Wisconsin | 53.31 | 46.39 | 60.23 | Harris |

Again focusing on the 13 “competitive” races, the model predicts that Harris will win 12 out of the 13 states, while Trump only wins Texas. This is the same finding as the first run of the state model from last week’s blog, although the prediction intervals are slightly smaller with overall lower predictions (e.g. last week’s model predicted Harris to win Georgia at 53.20% vs 51.85% this week). This week’s inclusion of October polling averages may suggest focusing more on late-stage polling when making predictions. Again, I’ve only included October polling data up to the writing of this blog (October 10, 2024).

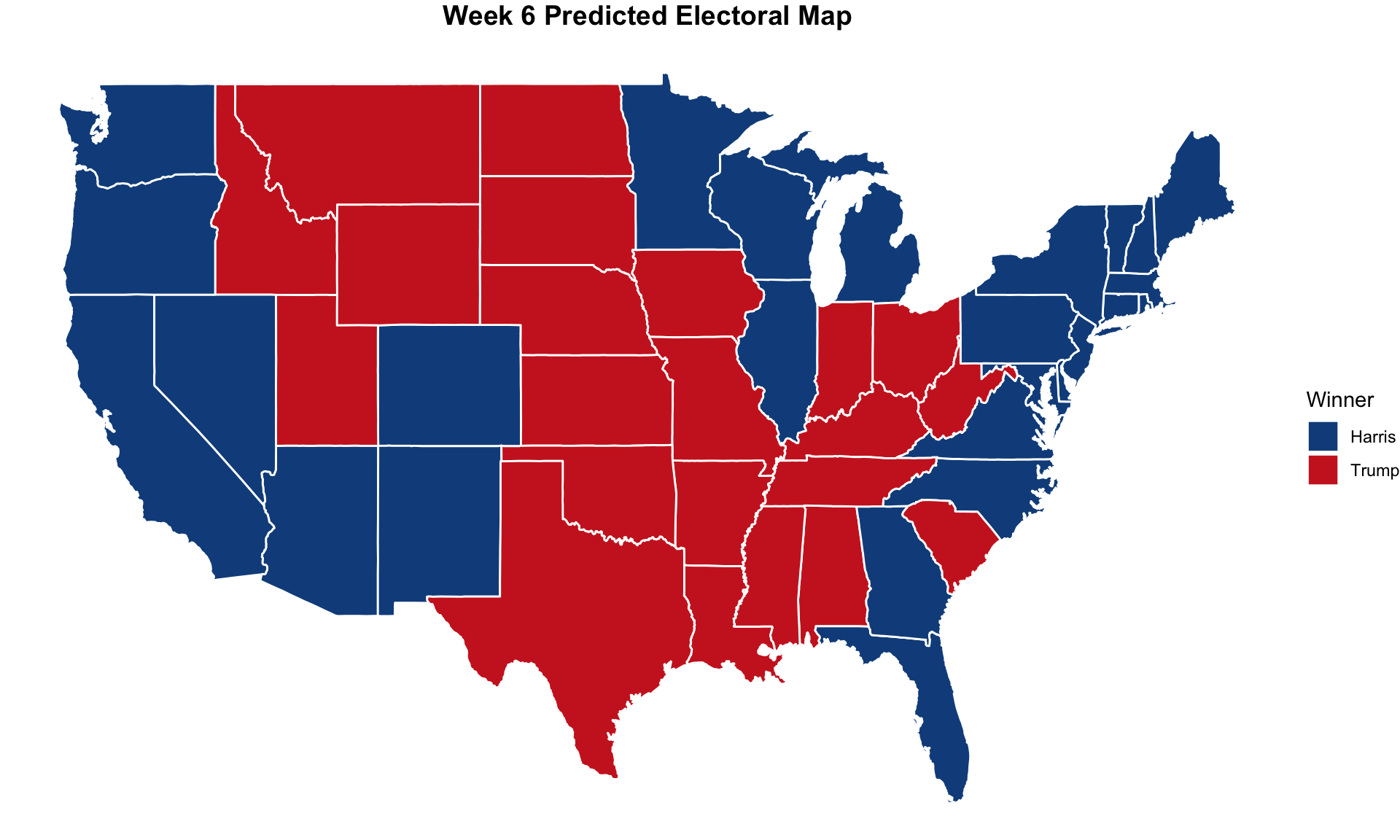

I also visualize my state-level predictions in a potential Electoral College map. Incorporating back in the other states (excluded as they are confident calls for either Harris or Trump), I get the following map!

More concisely, here are the tallied Electoral College votes for both candidates using this week’s state model.

| Candidate | Electoral College Votes |

|---|---|

| Donald Trump | 189 |

| Kamala Harris | 349 |

Conclusion

Once more, Harris is predicted to win both the national two-party popular vote and the Electoral College (by a margin of 349-189). I remain unconvinced that Harris will win Florida, but the rest of the state predictions seem quite plausible to me — especially given the close nature of all the swing state races. Perhaps I’ll turn to simplifying my models in the handful of blogs that remain. Additionally, I really enjoyed diving deeper into past campaign ad spending and the “air war” this week.